LGI’s Vincent Chauvet takes the Model X for a test drive.

One billion hours per day. This is the estimated time spent driving worldwide. In the US alone, the collective annual commuting time amounts to nearly 3.5 million years.

In my view, autonomous driving (AD) promises to give back commuters and drivers their most valuable resource: time. Incidentally, other promises of the AD revolution are nothing minor: ending traffic congestion, massively liberating urban areas of their parking spaces, getting rid of air pollution by supporting the uptake of electromobility (or rather displacing the city’s air pollution to wherever and however the electricity is produced), enabling inclusive mobility for non-drivers (including the disabled, elderly, teenagers…), significantly reducing the cost of mobility, and virtually eliminating accidents caused by human error. That’s not to mention the market is estimated to reach USD 60bn by 2030.

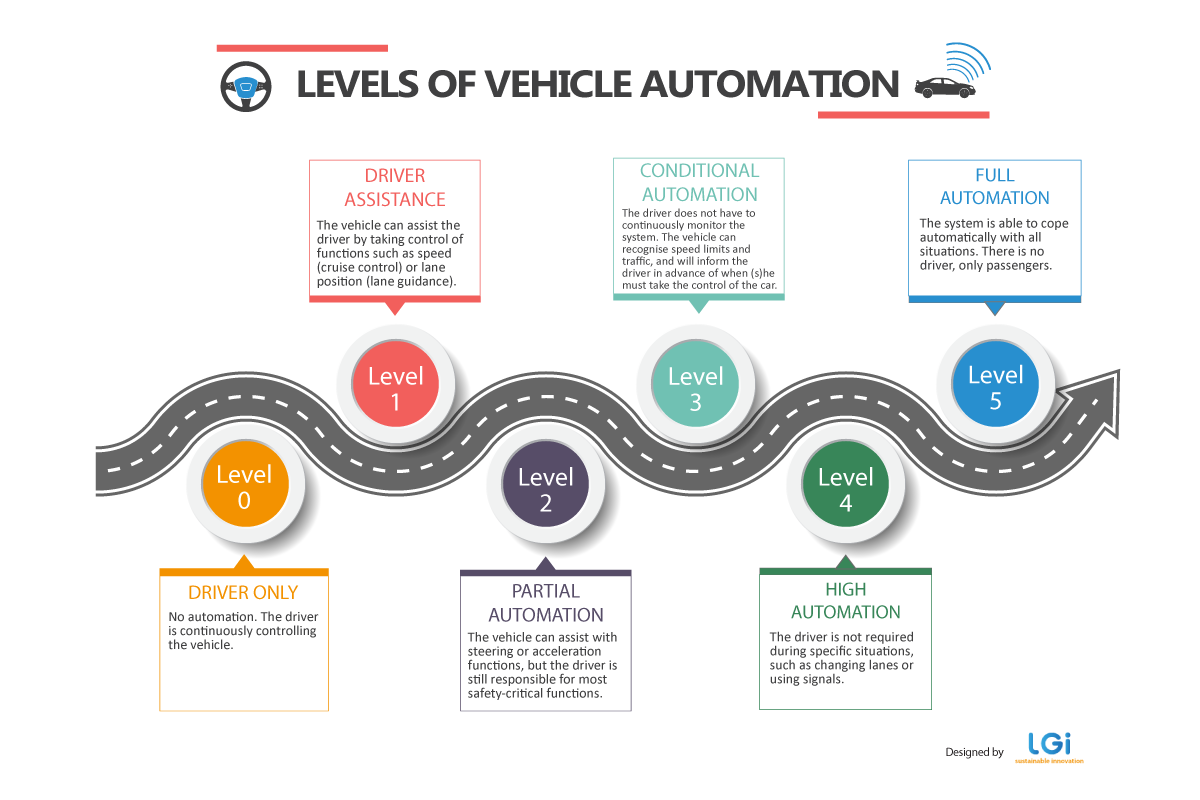

The stakes are massive. But are we ready for it? Letting go of a steering wheel, something we’ve clung onto for a century, seems in contradiction with the ever-increasing safety constraints for road transport. I recently participated in an experiment designed to analyse driver (or shall we say non-driver!) behaviour within a partially-autonomous car. The test took place with a Tesla Model X in a real environment, on The Francilienne, a high-speed road surrounding Paris. This was part of a research project called BRAVE, which stands for “BRidging gaps for the adoption of Automated Vehicles,” and which looks into user acceptance for AD. The test was organised locally by the mobility cluster Mov’eo and transport testing company UTAC CERAM. The Model X reaches level 2 on the international scale for driving automation (“partial automation”). Concretely, I let the car drive itself while on the 110 km/h road in the midst of mid-afternoon traffic (neither congested nor empty), with other cars leaving and entering the flux.

I have to say, the feeling of being behind the steering wheel, at more than 100 km/h, without actually driving, really was a new and exciting experience. The car adjusted its speed to traffic and followed the road curves rather seamlessly. The speed is capped manually by the user, and not automatically by the authorised limit in a given area. This appears as a strange conception choice, as it imposes a manual operation with each speed limit change, which is exactly how we behave with our manual vehicles, but which we don’t expect to have to do with an autonomous car. Keep in mind, however, that this was a level 2 (partial automation) car and not a level 5 (full automation) car.

I found myself repeatedly turning backwards to chat with my passengers, and left the steering wheel entirely for several minutes (until the car reminded me I shouldn’t do that). I look forward to learning from the results of the BRAVE project (expected to be published here by autumn 2018). The conclusion of this test is that I am now even more optimistic about the technology than I already was, and as a frequent driver of non-autonomous vehicles, I am quite looking forward to the “free-time promise.”

VINCENT CHAUVET

Founder and CEO

Meet me on LinkedIn

About Mov’eo

Mov’eo is a French Mobility and Automotive R&D competitiveness cluster. Since 2006, it has been mobilising to meet the objectives for competitiveness clusters, as assigned by the State: to foster the development of collaborative projects between members, to contribute to the development of companies (in particular SMEs), and to promote innovation in the sector. LGI has been a member of Mov’eo since 2014.

About UTAC CERAM

UTAC CERAM is a private, independent group providing services in all areas of land transport: regulation and approval, testing and technical expertise (environment, safety, durability and reliability), certification, events and driver training.

About the BRAVE project

Coordinated by Treelogic, BRAVE is an EU collaborative research project that is cofounded under the Horizon 2020 framework programme. BRAVE’s approach assumes that the launch of automated vehicles on public roads will only be successful if a user-centric approach is used where the technical aspects go hand-in-hand in compliance with societal values, user acceptance, behavioural intentions, road safety, and social, economic, legal and ethical considerations.

The views and opinions expressed in this blogpost are solely those of the original author(s) and/or contributor(s). These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of LGI or the totality of its staff.

FOLLOW US